I hold heterodox views on teaching writing. In brief, the way we teach writing in K-12 largely prepares students for further academia and not actual life. For example, I don’t use MLA (or APA) citations in my everyday life; you likely don’t either. I haven’t used them since grad school. When I want to cite a source, I use a hyperlink, occasionally a footnote.

When it comes to writing tasks, many teachers are obsessed with page and word counts. I try me best to avoid them. When I assign a task to a student, I tell them how many ideas or arguments they need to present, not how much to write. If a student can make a coherent argument for the abolition of the filibuster in the Senate, using two arguments, some evidence, and a counterclaim in 800 words, great! Oh, you need 1800 words? Fine. In the end, I care more about the ideas my students are interrogating than about the volume of writing they produce.

Writing instruction should ideally center on real-life use cases. They need opportunities to play with complex ideas rather than writing fewer, longer high-stakes pieces. I’ve been paid to write. Definitionally, I am a professional writer (don’t laugh). In all the occasions I have been paid to write something, it’s never been much more than 1000 words. If that’s good enough for Slate, it should be good enough for an IB/AP/A-Level comp class.

Now before you start erecting guillotines… Yes, students need to write and revise more often. Yes, they need to be taught to write for specific purposes and contexts (a wedding toast, a resume, a cover letter). But if a high school student can craft a coherent, thoughtful 1000 word essay, they’re in good shape. More isn’t better, it’s just more.

Lastly, almost all the writing my students do in class is hand-written, on-demand. I give them a prompt and some stimulus (a map, a data set, a passage from a primary source) and they go to town for the period. But in each class I teach, there’s usually also one longer, more formal essay each year where students are required to demonstrate more traditional essay skills. I really don’t enjoy reading or grading them, but I understand the exercise has some value.

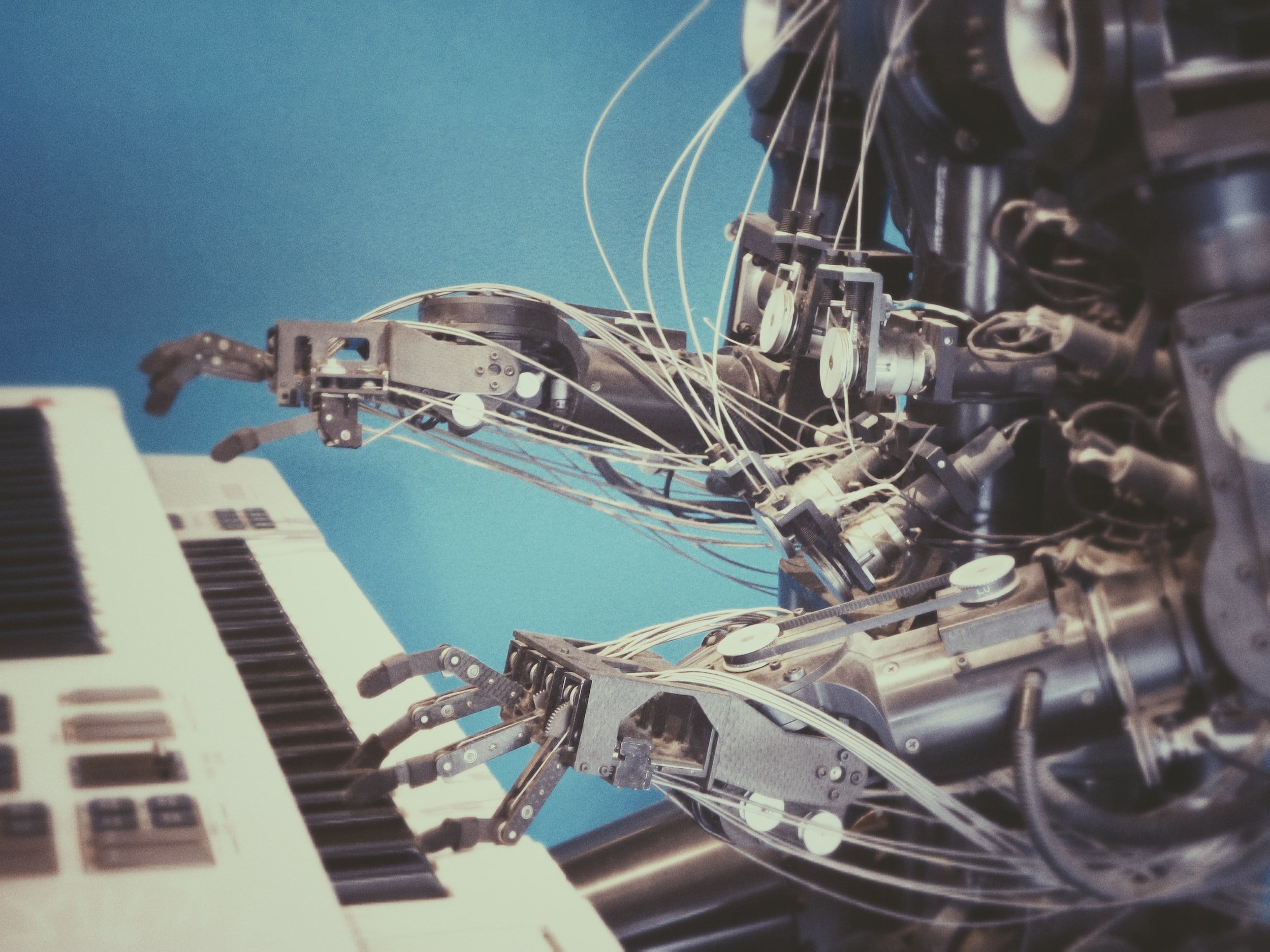

The preceding was my philosophy on writing until last week when that silly chat bot rolled into room 157.

Real talk, I am never assigning another out of class essay as long as I live. Ain’t no way in hell I’m gonna throw away my evenings and Sunday afternoons trying to figure out if the essay I am reading is Charlie’s or a chatbot. Nope, nein, nada—that is for suckers. I ain’t no sucka.

But it’s bigger than that. The emergence of AI created content onto the mainstream of our society with essentially no public debate or government regulation is incredibly problematic. Even worse, Open AI, the creator of ChatGPT (this is the only time I will use the name of the bot in question because every time you mention them you’re advertising for them), was co-founded by the problematic richest man on the planet, Elon Musk. Even worse squared, another co-founder, Sam Altman, was behind a massive crypto scam, Worldcoin. It promised to provide a form of UBI by collecting iris scans from half a million people in developing states in exchange for a crypto token that now trades at $0.02221. I am not making this up—this is possibly the worst idea ever, carried out by the worst people possible.

To be clear:

I want nothing to do with it.

Burn it with fire.

Let it fall forever in the Mines of Moria with the Balrog that killed Gandalf.

If you think I am being extreme here, that’s okay. Most people I talk to about this topic say the same. I got called a luddite for this take on my own podcast Friday night.

Here’s the thing. Philosophically, when I am presented with a moral question, I assume the “most likely, worst case scenario” and work backwards in crafting my personal response and preferred public policy outcome. For example, should we arm teachers? Well, do you want a racist Karen teacher that “fears for her life” shooting a Black middle schooler? No? Me either. So that’s a rubbish idea. Next, do we want the coverage of the upcoming election to be a torrent of partisan AI crafted propaganda and foreign-funded AI disinformation? If your answer is no (and unless you’re a psycho or a libertarian tecno-triumphalist, the answer should be no), we have to ask ourselves how do we prevent this dystopian hellscape scenario from taking place?

That’s where my conversations about mainstreaming AI start. Some of these pieces coming out from teachers about how they plan to integrate the bots in their practice are the most naive non-sense I’ve read in my whole life. Obviously, AI and machine learning are coming and have a place in our future. But do we have to let some of the worst people on the planet implement it with literally no regulatory checks, foresight, and the absence of an inclusive societal discourse? That’s just silly but not as silly as assigning the same tired essay prompts in 2023.